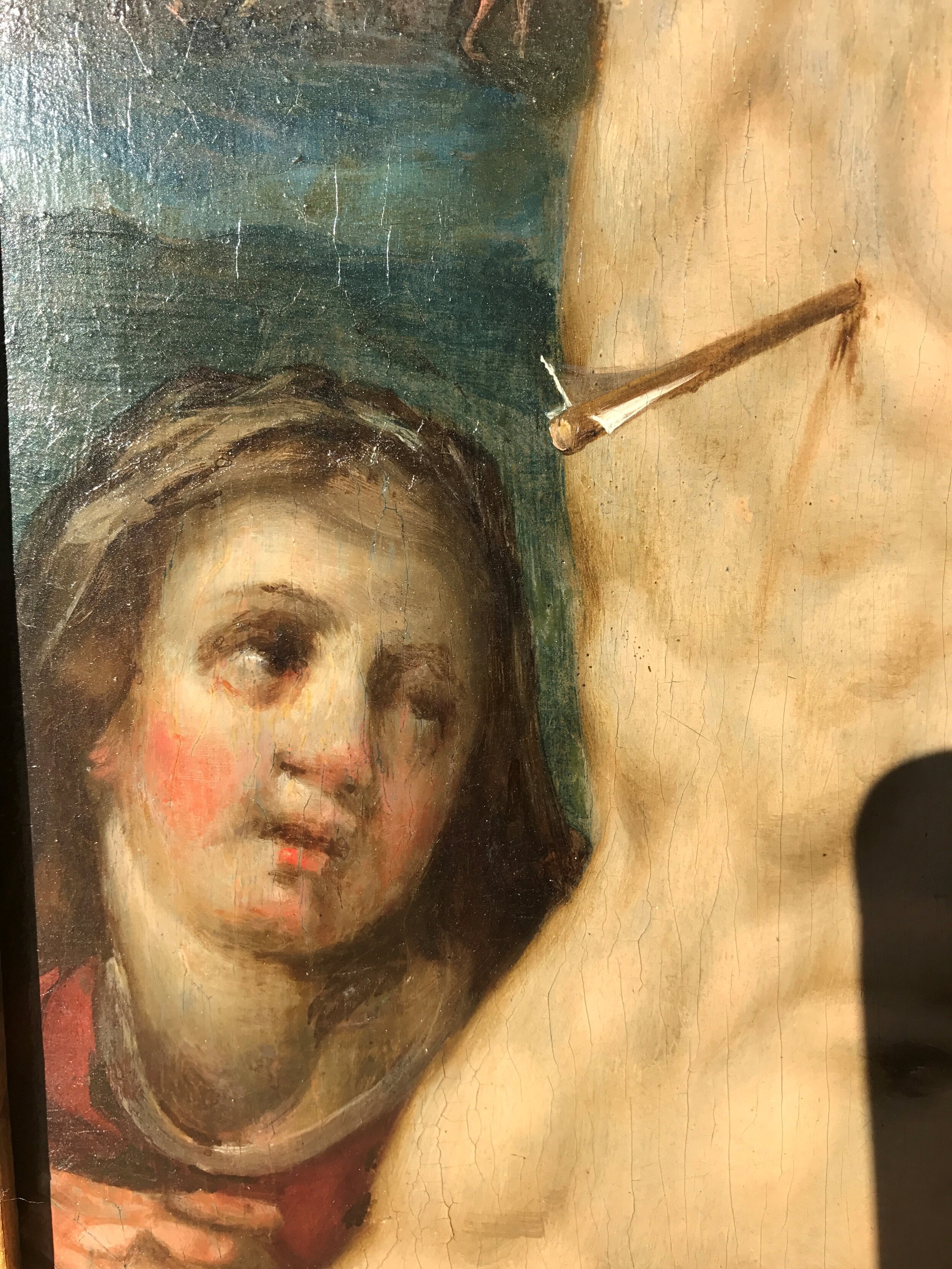

Michiel COXIE (1499-1592, Flemish)

Saint Sebastian

c. 1590

Oil on panel

Framed 20 x 15.75 inches

Price: Price on Application

Typical of the Mannerist obsession with virtuosity and complexity are the twisting poses, the high finish and the obsession with detail in the rendering of the muscles. Saint Sebastian was a Roman legionary martyred for his Christian beliefs. Since he was pierced with arrows, he became the patron saint of archers. Saint Sebastian was often depicted as a nearly nude young man. It would be easy to dismiss the plethora of works portraying his story simply as a means for early and high Renaissance artists to flaunt their capabilities in representing an idealised human form.

Another possibility for the idealised manner in which Saint Sebastian was depicted throughout the Renaissance is the idea that Saint Sebastian was an offering to God and should therefore be shown as the best offering possible. Sheila Barker acknowledges this idea by arguing that as “it was a widely accepted principle that the more precious the offering, the more God would be placated, [therefore] the attractiveness of Sebastian’s imagery may have been regarded as a factor in attaining divine mercy.”

This panel is likely to be a precursor to Coxcie’s larger painting of the Martyrdom of Sebastian for St Rumbold’s Cathedral in his home town Mechelen, Belgium, the same building where he died after falling from scaffolding whilst working. The poses of St Sebastian are similar, as is the highly respectful attention to botanical detail in the leaves on the trees. Both paintings celebrate Coxcie’s nickname as the Flemish ‘Raphael’, with his inscription of an ‘R’ on the tree. However, our panel is a more intimate depiction, parading Coxcie’s unbridled mastery in the classicised human form. Despite the limpness and deathly palour of the figure, Coxcie’s portrayal of St Sebastian still shows a visceral force and beauty that shows off Coxcie’s highly skilled classical training from his time working in Rome. Coxcie’s rendering of St Sebastian’s body is strongly evocative of Raphael and Michaelangelo’s muscular sculptural forms, and his soft treatment of St Cecile’s face is reminiscent of Raphael’s portrayal. This affirms Coxcie as a cultured and humanistic artist, who sensed the spirit of the age and celebrated it in his masterful compositions.

The figure of St Sebastian is consistent with the Italian style and shows an artist who has fully understood the basic principles of Italian renaissance painting. But the composition is not purely Italian because Coxcie depicts the saint in a typically Flemish landscape. In terms of perspective and anatomy, sixteenth-century Italian painters led the field. But when it came to painting landscapes, depicting textiles and other matter, the Low Countries were by far the best and their use of colour was unrivalled. This little work by Coxcie shows a master who bridged the gap between the two schools of painting. He uses the best of both worlds and integrates it into his own synthesis of the Renaissance.

Michiel COXCIE (Coxie, van Coxcie or de Coxien) was born in 1499 in Mechelen in the Duchy of Brabant. Though few people today are familiar with his name, Michiel Coxcie was probably one of the most important painters in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century. His nickname, the “Flemish Raphael”, illustrates just how highly his art was rated. Hence the ‘R’ on the tree in this painting of Saint Sebastian and many of his other works. He was compared to the greatest Renaissance master and regarded by some as his match. The position Coxcie occupied was on a par with that of Rubens and other great masters. Coxcie was born at the end of the fifteenth century and died in 1592 at the age of 93 following a fall from scaffolding. He was restoring one of his paintings in the Town Hall in Antwerp when he lost his balance. So his career spanned almost the whole of the tumultuous Sixteenth Century: from the Reformation and the Iconoclasm to the Catholic Counter-Reformation. Coxcie invented designs for tapestries, stained glass windows, prints and he also executed paintings, which are dispersed in collections around the world. He was widely travelled, worked in Rome, Brussels, Malines, and Antwerp. He was praised by Vasari for having taking the Italian manner to the Netherlands. He became a popular court artist and was commissioned by royalty and politicians all over Europe including, the King Phillip II of Spain, the Duke of Alva, Guido Morillon and Cardinal de Granvelle and Mary of Hungary to name a few.

Artistically he was a living link between the Flemish Primitives and the Baroque. When he was born, Gerard David was still active and Hieronymus Bosch (ca. 1450-1516) was at the height of his powers. When Coxcie died, Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was training in Antwerp. Coxcie trained in Bernard van Orley’s studio in Brussels in the 1520s, then moved to Italy where he was to spend about ten years studying the art of classical antiquity and mastering the style of the High Renaissance. During those years in Rome he came into contact with Vasari and Michelangelo and his reputation earned him commissions in the Church of Santa Maria dell’Anima and St Peter’s Basilica. Recognition of his work brought him membership of the Compagnia di San Luca in Rome, an honour conferred on no other Fiamminghi before him. In 1539 he returned to the Netherlands, a Messiah of Renaissance art. Almost immediately he became the favourite of Charles V and Margaret of Hungary and in that capacity he was given the honour of, for example, working with Titian on tapestries for the Royal Palace in Binche.

Coxcie designed many tapestries and stained-glass windows for the Hapsburg dynasty. For Philip II he painted the famous copy of the Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb). During the first decades of the Dutch Revolt (1568-1648) Coxcie sided resolutely with the Catholics. After the Iconoclasm that decision brought him commissions for scores of new altarpieces in (among other places) Antwerp, Mechelen and Brussels. Few commanded so much respect as Coxcie and few had so much influence on their contemporaries. Even in the Seventeenth Century, artists – and not least Rubens - reworked his inventions.

Coxcie laid the foundations on which great masters like Rubens and Van Dyck later built their reputations. In the Sixteenth Century Flanders was in the spotlight of political developments and the centre of trade in Northern Europe. It was the place where the new ideas of Erasmus, Lipsius and more came to light. Brussels was the Mecca for tapestry production and achieved a level of excellence that would never again be equalled. The very first international art market developed in Antwerp. But then we arrive at an extraordinary conclusion: these days paintings from sixteenth-century Flanders are almost unknown.

Michiel Coxcie is one of those artists whose name disappeared into the annals of history. Coxcie acquired great fame in the years he spent in Italy, where he had access to the most notable art collections and was a member of Michelangelo’s small exclusive circle. In the decade he spent in the Eternal City, he saw and studied so much that he not only fully understood the style of the High Renaissance, but he also became thoroughly acquainted with the classics. This knowledge shaped him as an artist and was to make him one of the great masters of the Sixteenth Century.

Karel van Mander, the Flemish Vasari, tells us in his influential ‘SchilderBoeck’ (Book of Painters) that Coxcie’s best works were abroad like this panel of Saint Sebastian. It seems it was a lucrative activity to buy Coxcies in the Netherlands and sell them abroad at a great profit. Consequently, numerous masterpieces are found in art collections in Spain and Germany. Coxcie died in 1592 after falling from scaffolding whilst painting in a church. He left behind his son Raphael, also a painter and his wife Ida.